Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

skip to main |

skip to sidebar

Gunned Down & Murdered In Tehran June 20, 2009. A Book About Death Supports A Free Iran.

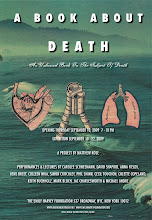

A BOOK ABOUT DEATH : ARTISTS CONTRIBUTE 500 POST CARDS EACH TO CREATE AN UNBOUND BOOK ABOUT DEATH. EXHIBITION AT THE EMILY HARVEY FOUNDATION GALLERY IN NEW YORK CITY. OPENING: THURSDAY 10 SEPTEMBER 2009. EXHIBITION: 10 - 22 SEPTEMBER 2009. TUES - SAT 1 PM - 7PM.

About Me

PRESS ARTICLES

Viv Maudlin Film

GRACE GRAUPE-PILLARD FILM

A Book About Death from Grace Graupe Pillard on Vimeo.

Jac Charlesworth Film

Honey Millman Film

IMPORTANT LINKS

LIVE WEB CAST 6 PM SEPT 10, 2009

A BOOK ABOUT DEATH

A BOOK ABOUT DEATH : ARTISTS CONTRIBUTE 500 POST CARDS EACH TO CREATE AN UNBOUND BOOK ABOUT DEATH. AN HOMAGE TO RAY JOHNSON, A CELEBRATION OF EMILY HARVEY, A GLOBAL EXPLORATION OF DEATH.

NO LIMIT TO THE NUMBER OF ARTISTS CONTRIBUTING. CDs, DVDs & OBJECTS ACCEPTED - SEND 500. DEADLINE: SEPTEMBER 5!

EXHIBITION AT THE EMILY HARVEY FOUNDATION GALLERY IN NEW YORK CITY. OPENING: THURSDAY 10 SEPTEMBER 2009. EXHIBITION: 10 - 22 SEPTEMBER 2009. OPENING : 7:30 - 11 PM.

PROJECT SPONSORS

NEDA SOLTAN

Gunned Down & Murdered In Tehran June 20, 2009. A Book About Death Supports A Free Iran.

IMPORTANT: SENDING .JPG IMAGES FOR BLOG & SITE

IMPORTANT: ONCE YOU'VE COMMITTED IMAGES TO PRINT, SEND YOUR IMAGES TO MATTHEW.ROSE.PARIS@GMAIL.COM IN JPG FORMAT, SEND LARGE IMAGES (but not heavy in the megabyte sense). APPROX 900 x 600 PIXELS – OR 200K – FOR EACH IMAGE IS BEST. THIS PERMITS FAST LOADING ON THIS BLOG AND WEB SITE.

NOTE: YOU ARE NOT OBLIGED TO PUT IN THE VENUE INFO, ONLY THE TEXT : A BOOK ABOUT DEATH, ANY SIZE, ANY STYLE, ANY LANGUAGE. YOU ARE FREE TO CREATE WHATEVER YOU WISH. A POST CARD IS A PAPER MACHINE.

NOTE: YOU ARE NOT OBLIGED TO PUT IN THE VENUE INFO, ONLY THE TEXT : A BOOK ABOUT DEATH, ANY SIZE, ANY STYLE, ANY LANGUAGE. YOU ARE FREE TO CREATE WHATEVER YOU WISH. A POST CARD IS A PAPER MACHINE.

Followers

SUBMIT YOUR WORK TODAY

CLICK HERE FOR ALL INFO ON SUBMITTING YOUR WORK FOR THE OPEN ARTIST CALL : A BOOK ABOUT DEATH. PLEASE NOTE: DEADLINE SEPTEMBER 5.

SPONSOR THE EXHIBITION

We are looking for a dozen sponsors for the opening. What we need: 12 - 24 bottles of wine each. We will list you here and in the printed program. Get in touch. Doesn't cost much and you'll be famous and we'll love you. CLICK HERE : TO E-MAIL MATTHEW ROSE

SPONSOR THE EXHIBITION

We are looking for a dozen sponsors for the opening. What we need: 12 - 24 bottles of wine each. We will list you here and in the printed program. Get in touch. Doesn't cost much and you'll be famous and we'll love you. CLICK HERE : TO E-MAIL MATTHEW ROSE

WHERE TO SEND THE 500 POSTCARDS:

Send Cards Here (Exact Address):

The Emily Harvey Foundation

537 Broadway #2

New York City, New York 10012 USA

Tel +1 212 925 7651

The Emily Harvey Foundation

537 Broadway #2

New York City, New York 10012 USA

Tel +1 212 925 7651

PRINTING YOUR CARDS

You can produce your own cards, print them in your country, or use these:

1. GOT PRINT (US)

2. OVERNIGHT PRINTS (US)

3. UPRINTING (US)

FOR OVERNIGHT, TYPE IN CODE FOR DISCOUNT: POSTCARDSALE

1. GOT PRINT (US)

2. OVERNIGHT PRINTS (US)

3. UPRINTING (US)

FOR OVERNIGHT, TYPE IN CODE FOR DISCOUNT: POSTCARDSALE

Blog Archive

SPREAD THE WORD ABOUT A BOOK ABOUT DEATH

Twitter? Send the Artist Call For A Book About Death Out On Twitter. Blog? Write A Post. E - Mail the URL To Artist Friends. Press? Contact Matthew Rose Directly.

![THE PROGRAM [DOWNLOAD PDF]](http://1.bp.blogspot.com/_SAUcA31atjA/SqSHZfoppEI/AAAAAAAADUM/ehptv2xIp9Q/S220/PROGRAM+FLYER_DIVING+POSTER.1.jpg)

4 comments:

Count No Man Happy Until He Is Dead?

Simon Critchley’s recent piece, How to Make it in the Afterlife, immediately brought Matthew Rose and A Book About Death to mind.

It in the late 1970s, when we became friends, Matthew was studying Semiotics and I was studying Ancient Greek. I was reading parts of Herodotus’ History (tr. by George Rawlinson) in the original. In Book 1 of that work is found, as far as I know, the first textual record of the Ancient Greek ideal Critchley wrote about: one should count no man happy until he is dead.

It occurs in a conversation between Solon, the great Athenian lawgiver and wise man, and Croesus, emperor of the mighty empire of the Lydians and a man so wealthy that from his time straight to ours his name – lower case “c”, as a noun standing alone -- is a synonym for a wealthy man. At the peak of Lydian power, according to Herodotus, all the sages of Greece living at the time came to Sardis, the empire’s capital. Among them was Solon, who had left Athens to travel for 10 years “under the pretence of wishing to see the world, but really to avoid being forced to repeal any of the laws which, at the request of the Athenians, he had made for them. Without his sanction the Athenians could not repeal them, as they had bound themselves under a heavy curse to be governed for ten years by the laws which should be imposed on them by Solon.”

Croesus invited Solon to an audience, and, according to Herodotus, Croesus addressed this question to him. "Stranger of Athens, we have heard much of thy wisdom and of thy travels through many lands, from love of knowledge and a wish to see the world. I am curious therefore to inquire of thee, whom, of all the men that thou hast seen, thou deemest the most happy?" This he asked because he thought himself the happiest of mortals: but Solon answered him without flattery, according to his true sentiments, "Tellus of Athens, sire." Full of astonishment at what he heard, Croesus demanded sharply, "And wherefore dost thou deem Tellus happiest?" To which the other replied, "First, because his country was flourishing in his days, and he himself had sons both beautiful and good, and he lived to see children born to each of them, and these children all grew up; and further because, after a life spent in what our people look upon as comfort, his end was surpassingly glorious.

In a battle between the Athenians and their neighbours near Eleusis, he came to the assistance of his countrymen, routed the foe, and died upon the field most gallantly. The Athenians gave him a public funeral on the spot where he fell, and paid him the highest honours."

Solon explained that two other men were happier than Croesus: Klobis and Biton, brothers who had died in their sleep after their had prayed mother for that they be granted “the highest blessing to which mortals can attain.”

MORE-----------

CONTINUED...

While Critchley draws from the idea the Ancient Greek belief that public regard is more important that personal gratification, the idea always appealed to me as an archetypical lesson in hubris. Humility is necessary because no matter how rich and glorified you are, disaster can strike. (See, e.g., Bernie Madoff; Steve Jobs; Michael Jackson; Elvis Presley).

That the point came up in connection with Croesus and Solon only emphasized this aspect of the story. Solon, whom the Athenians would have accepted as King, instead imposed his legal code and left to let his law, not his ego, rule. And Croesus, after his encounter with Solon was brought low. Croesus had two sons, “one blasted by a natural defect, being deaf and dumb; the other, distinguished far above all his co-mates in every pursuit.” The latter insisted on being part of a hunting party sent out to relive the region of a wild boar’s ravages. Afraid for his son, Croesus insisted that Adrastus, whom Croesus had previously purified and thus cured of an affliction, be part of the hunting party. As Croesus explained to Adrastus, Adrastus should go to watch over Croesus’ son and “’if perchance you should be attacked upon the road by some band of daring robbers. Even apart from this, it were right for thee to go where thou mayest make thyself famous by noble deeds. They are the heritage of thy family, and thou too art so stalwart and strong.’"

When the party encountered the boar, Adrastus hurled his spear, which missed the boar but struck and killed Croesus’ son.

Soon after a period of intense grief, Croesus received intelligence of the rising power of the Persians under their king, Cyrus. Intent on cutting them down before they became too powerful, he sent messengers to the oracle at Delphi asking what he should do. The oracle answered that “if Croesus attacked the Persians, he would destroy a mighty empire.” And so he attacked the Persians, and was defeated, thereby bringing about the destruction of his own mighty empire.

MORE---------

CONT..

The story is of particular importance to Herodotus because he wrote his work not long after the Greeks had miraculously defeated the Persians, by then the world’s lone superpower, the event that sparked the brief glory of Classical Athens and that forever since established the template of the world’s division into East and West. Herodotus’ message was, no doubt, intended in part as a moral lesson to the Athenians not to take excessive pride in their flowering success, a lesson that, of course, was in a very brief time ignored, bringing Athens to its fall only half a century later.

But as a lesson about death? What happiness for anyone lies in someone’s death at the peak of their success?

Just this past winter events convinced me there is none. A very good friend of mine with whom I practiced law in New York City for many years finally quit in the early Nineties, against the advice of virtually everyone, to pursue his dream of opening a restaurant. He became a fantastically successful restaurateur in NYC. He got married at age 48. At 49 his wife had their kid. On his 50th birthday last December he toasted everyone he had invited to home, explaining that he had everything he had ever wanted in life and that he wanted them all to know how grateful he was for it and to everyone there. That night at 4am his wife heard a thump. He had fallen out of bed and was lying on the floor next to it, dead.

There is no doubt his death highlighted to all who knew him well how extraordinary he was. Kind and generous without any guile to his friends and loved ones, and full of a vitality and enthusiasm that, on reflection, seemed remarkably free of egotism. But even if his death made us realize these things we always knew but perhaps hadn’t dwelled upon, it is impossible to believe that his death, exactly at the moment Solon would have deemed the one that would bring ultimate happiness, increased the world’s happiness in any way whatsoever.

Peter Friedman

Visiting Assistant Professor

University of Detroit Mercy Law School

Associate Professor, Legal Analysis & Writing

Case Western Reserve University Law School

E: peter.friedman@case.edu

http://blogs.geniocity.com/friedman/

Your artwork has been received at the Emily Harvey Gallery

Post a Comment